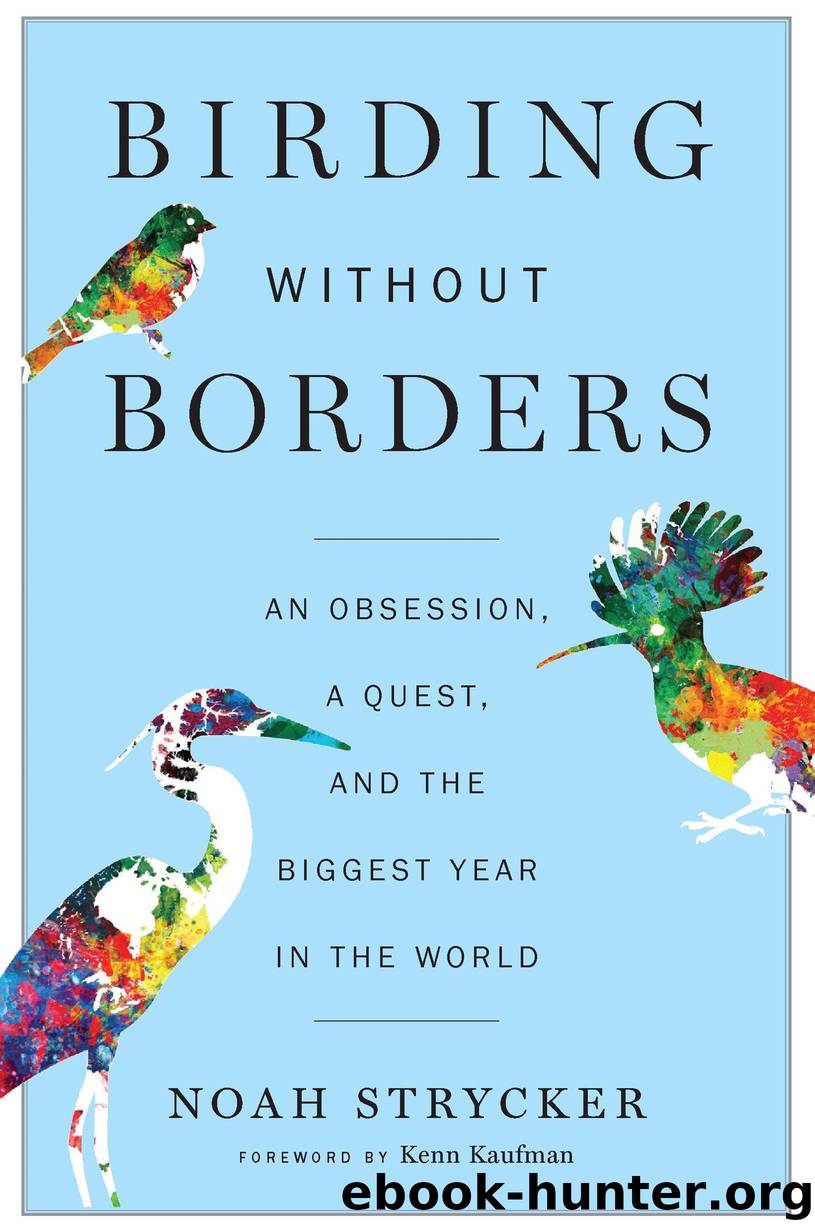

Birding Without Borders by Noah Strycker

Author:Noah Strycker

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

✧-✧-✧

Two days later, on September 16, Harsha and I arrived at the Thattekad Bird Sanctuary, a lowland forest patch along the Periyar River, at first light. With twenty-seven species to go to the record, we met a local birder named Sanu Sasi, who knew the area’s birds like the back of his hand. The three of us entered the sanctuary in lively spirits.

Soon after dawn, a convoy of vehicles pulled up: the Ezhupunna Birders, a group of about a dozen young and enthusiastic bird lovers, had heard about my quest and wanted to help. They had driven two hours from the city of Kochi, having risen early to make the trip, and spilled out in a gaggle of smiles and handshakes.

With more than a dozen eager pairs of eyes in the forest, the birds had little chance of hiding. A Malabar Trogon, cherry red underneath with a black head and a thin white border encircling its neck, surveyed our group with apparent amusement from a high branch. Sanu pointed out a couple of Flame-throated Bulbuls, greenish yellow with black heads and orange throats, while Dark-fronted Babblers squeaked and rattled from the nearby undergrowth. Several White-bellied Treepies, a flashy and long-tailed member of the crow family endemic to southern India, called noisily from the forest, eventually affording great views while crossing a gap between trees. The birding was so brisk that I could barely keep up, and the morning hours flew by with more than twenty new species.

By noon, I was counting down single digits: a tiny Heart-spotted Woodpecker, black and white with a spiky crest and practically no tail, put me within ten species of surpassing the record; and after several more sightings, a White-rumped Needletail, a type of swift, sliced the gap down to five. But then, with the record dangling so close, activity stalled. In early afternoon a discouraging, drizzling rain began to fall, birds stopped singing, and it seemed that we might not reach the hoped-for number that day after all.

The Ezhupunna Birders reluctantly clocked out for lunch, wishing luck to Harsha, Sanu, and me. With rain pounding, we held a quick strategy session under the shelter of a leaky, unoccupied hut. Sanu suggested that we look for some common water-loving species near his house a few miles away, so we spent the next couple of hours in a downpour, tramping back and forth across a grassy field; one by one, we managed to see a White-rumped Munia, a White-breasted Waterhen, and a flyover Gray-fronted Green-Pigeon, endemic to this part of India. Now I was one tantalizing species away from tying the world record.

“Hey, I just saw a Common Iora!” yelled Harsha, who was staring at a patch of low trees a couple hundred yards away. “Come on, I think it just zipped out the other side.”

The three of us sloshed across the field to catch up with the bird, my heart pounding with excitement and exertion, but the iora—a sparrow-sized, yellowish green songbird with black-and-white wings—proved flitty and elusive.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Photographic Guide to the Birds of Indonesia by Strange Morten;(2533)

The Big Twitch by Sean Dooley(2436)

7-14 Days by Noah Waters(2418)

Tippi by Tippi Hedren(2236)

Identifying Birds by Colour by Norman Arlott(2185)

Birds of the Pacific Northwest by Shewey John; Blount Tim;(1975)

Penguin Bloom by Cameron Bloom(1933)

The Path Between the Seas by David McCullough(1614)

Raptors by Traer Scott(1603)

Life on Earth by David Attenborough(1504)

Bald Eagles In the Wild by Jeffrey Rich(1483)

Skin by Unknown(1420)

The Natural Sciences: A Student's Guide by John A. Bloom(1403)

How to Speak Chicken by Melissa Caughey(1334)

The Feather Thief by Kirk Wallace Johnson(1287)

Nest by Janine Burke(1275)

An XL Life by Big Boy(1221)

H Is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald(1205)

Life List by Olivia Gentile(1191)